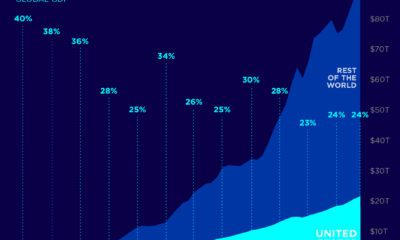

Examining a country’s economic building blocks can tell us a lot about what stage of development the country is in, and where competitive advantages may exist.

Analyzing GDP by Sector

Today’s “horse race” bar chart, by Number Story, is an entertaining historical look at the ranking of top countries by GDP, including the parts that make up the whole. Here is the latest data as of 2018, as well as the largest sector according to data from the United Nations’ industry classification database: Why are “Other Activities” so dominant in this breakdown? It’s because of the way GDP that components are classified as data in the UN industry classification system, which is laid out below: Although agriculture, construction, or manufacturing have been a bedrock for economies in the past, developed countries skew towards adding economic value in different ways today. Given that finance, government spending (healthcare, education, defense, etc.) and technology — all important modern industries — are included in “Other”, this makes the possibly outdated classification the biggest (and least useful) category to examine here. Nevertheless, there is still information we can glean from this animated breakdown of GDP, spanning a period of almost 50 years.

A More Granular Look at GDP

In the past, we’ve shown you high level visualizations that break down the world’s $86 trillion GDP by country, or even projections on the largest countries by GDP in 2030 in PPP terms. However, the animated bar chart shows something more granular that is compelling in its own right. By observing the evolution of countries’ economic components over time, some interesting observations emerge that would normally be lost in the big picture.

Japan’s Manufacturing Boom

At points during Japan’s heyday of growth during the 1980’s, manufacturing comprised nearly 30% of economic activity. By the mid-90s, this single segment of Japan’s economy was so valuable that, on its own, it would’ve placed fifth in the global ranking.

America Leading the Pack

While other countries switch positions, reordering as economies boom and bust, the U.S. has handily remained in top position. Japan was the country that narrowed the gap between the first and second spot the most, though the country’s Lost Decade in the 1990s cut that ascension short. During the years between 1970 and 2017, the United States was at its most dominant in 2006 when its GDP was triple the size of Japan’s. Of course, in recent years China has narrowed the gap considerably.

A Star Rising in the East

As one would expect, the building blocks of China’s economy looked very different in the 1970s than today. The communist systems of the USSR and China are both easy to spot in the visualization. Agriculture played an outsized role, and industries like finance, real estate, and retail were understated compared to the profiles of countries that operated under a capitalist system. In 1980, as the first Special Economic Zones were being created, three-quarters of China’s economy was based on agriculture, resource extraction, and manufacturing. Even as recently as the early ’90s, China wasn’t in the top 10 despite being the world’s most populous country. Of course, that situation changed drastically over the next two decades. By the dawn of the 21st century, China ranked fifth in the world, and a decade later, China surpassed Japan to become the second largest economy globally. on Last year, stock and bond returns tumbled after the Federal Reserve hiked interest rates at the fastest speed in 40 years. It was the first time in decades that both asset classes posted negative annual investment returns in tandem. Over four decades, this has happened 2.4% of the time across any 12-month rolling period. To look at how various stock and bond asset allocations have performed over history—and their broader correlations—the above graphic charts their best, worst, and average returns, using data from Vanguard.

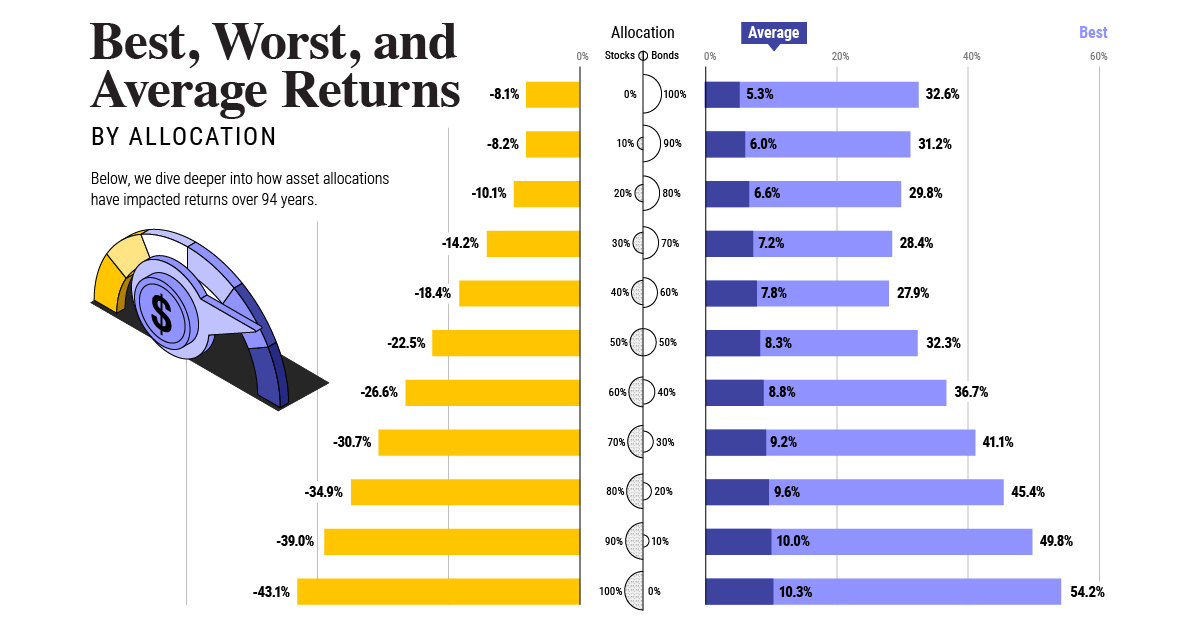

How Has Asset Allocation Impacted Returns?

Based on data between 1926 and 2019, the table below looks at the spectrum of market returns of different asset allocations:

We can see that a portfolio made entirely of stocks returned 10.3% on average, the highest across all asset allocations. Of course, this came with wider return variance, hitting an annual low of -43% and a high of 54%.

A traditional 60/40 portfolio—which has lost its luster in recent years as low interest rates have led to lower bond returns—saw an average historical return of 8.8%. As interest rates have climbed in recent years, this may widen its appeal once again as bond returns may rise.

Meanwhile, a 100% bond portfolio averaged 5.3% in annual returns over the period. Bonds typically serve as a hedge against portfolio losses thanks to their typically negative historical correlation to stocks.

A Closer Look at Historical Correlations

To understand how 2022 was an outlier in terms of asset correlations we can look at the graphic below:

The last time stocks and bonds moved together in a negative direction was in 1969. At the time, inflation was accelerating and the Fed was hiking interest rates to cool rising costs. In fact, historically, when inflation surges, stocks and bonds have often moved in similar directions. Underscoring this divergence is real interest rate volatility. When real interest rates are a driving force in the market, as we have seen in the last year, it hurts both stock and bond returns. This is because higher interest rates can reduce the future cash flows of these investments. Adding another layer is the level of risk appetite among investors. When the economic outlook is uncertain and interest rate volatility is high, investors are more likely to take risk off their portfolios and demand higher returns for taking on higher risk. This can push down equity and bond prices. On the other hand, if the economic outlook is positive, investors may be willing to take on more risk, in turn potentially boosting equity prices.

Current Investment Returns in Context

Today, financial markets are seeing sharp swings as the ripple effects of higher interest rates are sinking in. For investors, historical data provides insight on long-term asset allocation trends. Over the last century, cycles of high interest rates have come and gone. Both equity and bond investment returns have been resilient for investors who stay the course.