After being printed or minted, each bill is then passed between people and businesses to facilitate transactions. If it’s a $1 or $5 bill, it changes hands on average about 110 times per year – and if it’s a $20 bill, it’s more like 75. The interesting part is that almost every transaction is linked to the one before it, and the series of subsequent transactions for each bill creates a unique, broad story. By the time a bill is retired, it would have facilitated many hundreds of transactions that enabled everything from the purchase of used cars to the shadier deals in underground markets. It’s a pretty interesting tale for such a little piece of paper.

Dollar Bills, in Aggregate

Today’s infographic from TitleMax gives a sense of what happens when all of those individual stories are combined together into one large one: the U.S. supply of currency notes, the shelf life of each type of bill, and how the whole system works as a whole. In total, there is a total of about $1.5 trillion in U.S. physical currency in circulation, and roughly 80% of this value comes from the 11.5 billion $100 notes that are in circulation. Of course, as we showed in All the World’s Money and Markets, this is just a fraction of the total money that exists as a whole, which includes digital deposits and liquidity added by central banks. That’s why, in the U.S. today, there’s about $14 trillion in total money supply (M2), of which physical currency makes up only about 11% of the total value.

Turnover Per Bill

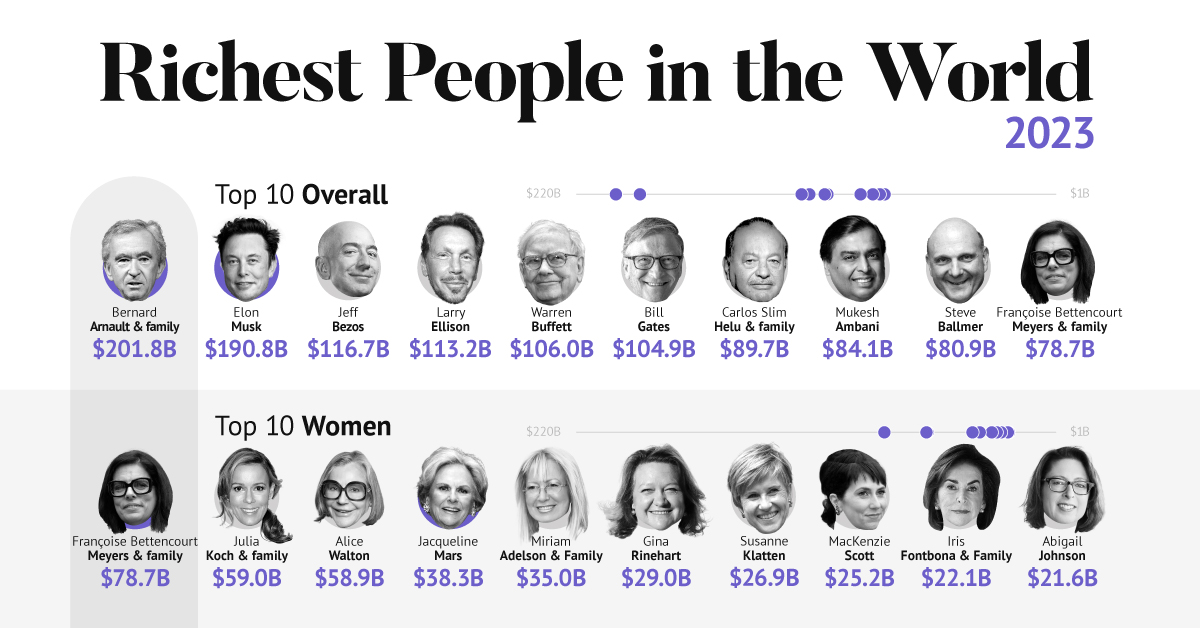

Every year, the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing is responsible for printing new dollars – and interestingly, 70% of these new bills are used to replace older notes going out of circulation. That raises the question: how long does each bill last on average? This means that printers are mostly turning out new batches of $1 and $20 bills, since there are more of those in circulation than most other bills. At the same time, many new $100 notes are also being printed as well since they are the second most common bill. However, these last 2-3x as long as smaller denominations. on A lagging stock market dented these fortunes against high interest rates, energy shocks, and economic uncertainty. But some of the world’s billionaires have flourished in this environment, posting sky-high revenues in spite of inflationary pressures. With data from Forbes Real-Time Billionaires List, we feature a snapshot of the richest people in the world in 2023.

Luxury Mogul Takes Top Spot

The world’s richest person is France’s Bernard Arnault, the chief executive of LVMH.

With 75 brands, the luxury conglomerate owns Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior, and Tiffany. LVMH traces back to 1985, when Arnault cut his first major deal with the company by acquiring Christian Dior, a firm that was struggling with bankruptcy.

Fast-forward to today, and the company is seeing record profits despite challenging market conditions. Louis Vuitton, for instance, has doubled its sales in four years.

In the table below, we show the world’s 10 richest people with data as of February 27, 2023:

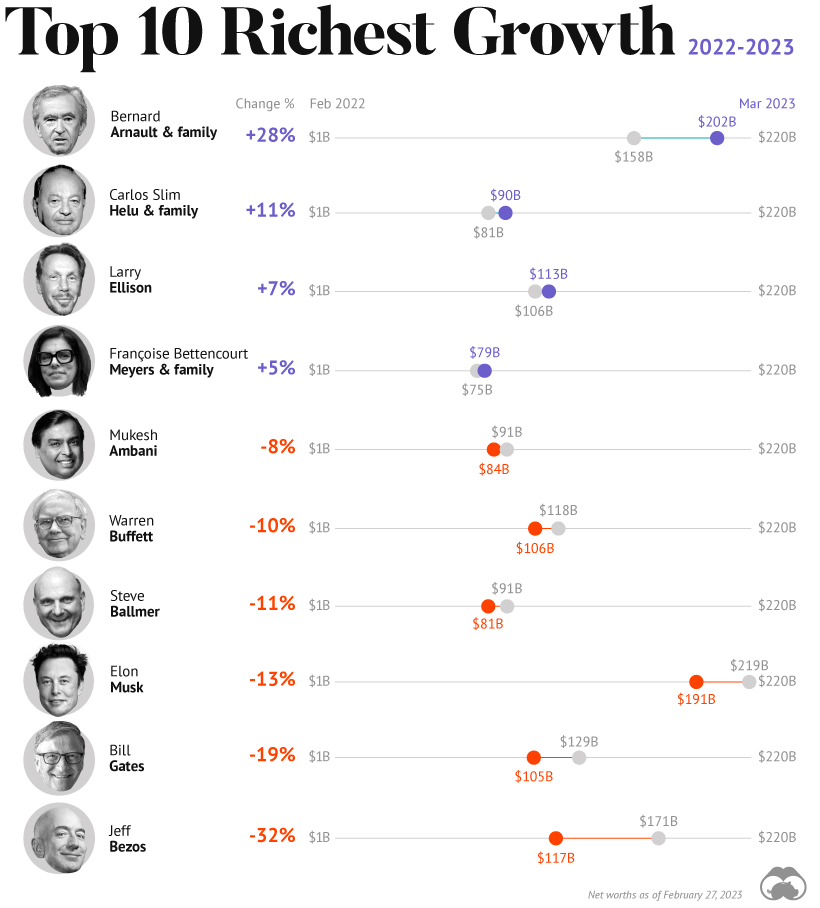

Elon Musk, the second-wealthiest person in the world has a net worth of $191 billion. In October, Musk took over Twitter in a $44 billion dollar deal, which has drawn criticism from investors. Many say it’s a distraction from Musk’s work with Tesla.

While Tesla shares have rebounded—after falling roughly 70% in 2022—Musk’s wealth still sits about 13% lower than in March of last year.

Third on the list is Jeff Bezos, followed by Larry Ellison. The latter of the two, who founded Oracle, owns 98% of the Hawaiian island of Lanai which he bought in 2012 for $300 million.

Fifth on the list is Warren Buffett. In his annual letter to shareholders, he discussed how Berkshire Hathaway reported record operating profits despite economic headwinds. The company outperformed the S&P 500 Index by about 22% in 2022.

How Fortunes Have Changed

Given multiple economic crosscurrents, billionaire wealth has diverged over the last year. Since March 2022, just four of the top 10 richest in the world have seen their wealth increase. Two of these are European magnates, while Carlos Slim Helu runs the largest telecom firm in Latin America. In fact, a decade ago Slim was the richest person on the planet. Overall, as the tech sector saw dismal returns over the year, the top 10 tech billionaires lost almost $500 billion in combined wealth.

Recent Shakeups in Asia

Perhaps the most striking news for the world’s richest centers around Gautam Adani, formerly the richest person in Asia. In January, Hindenburg Research, a short-selling firm, released a report claiming that the Adani Group engaged in stock manipulation and fraud. Specifically, the alleged the firm used offshore accounts to launder money, artificially boost share prices, and hide losses. The Adani Group, which owns India’s largest ports—along with ports in Australia, Sri Lanka, and Israel—lost $100 billion in value in the span of a few weeks. Interestingly, very few Indian mutual funds hold significant shares in Adani Group, signaling a lack of confidence across India’s market, which was also cited in Hindenburg’s report. As a result, Mukesh Ambani has climbed to Asia’s top spot, controlling a $84 billion empire that spans from oil and gas and renewable energy to telecom. His conglomerate, Reliance Industries is the largest company by market cap in India.